|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

from https://besharamagazine.org/arts-literature/james-lowe-the-art-of-conducting/

The Art of Conducting British conductor James Lowe talks about the nature of music, and the influence of the Tao Te Ching on his work  “There are times when something just descends and it’s impossible to describe… the music has brought us all to the same point.” When a conductor raises the baton and the orchestra begins to play, where is the music summoned from? In this interview, James Lowe, artistic director for the Spokane Symphony in Washington State, USA, talks about his career as a conductor, and what experience has taught him about the nature of music. James’s work as a conductor has ranged over five continents, including collaboration with orchestras in the UK and Europe, Japan, Australia and the USA, and he has studied with some of the world’s leading conductors, such as Bernard Haitink and Neeme Järvi. Jorma Panula called him ‘a remarkable orchestral conductor’. Charlotte Maberly and Robin Thomson spoke to him at his home in the Scottish Borders about his passionate belief that classical music is for everyone, and why in its ability to transcend language and speak universal truths, it is now more relevant than ever.

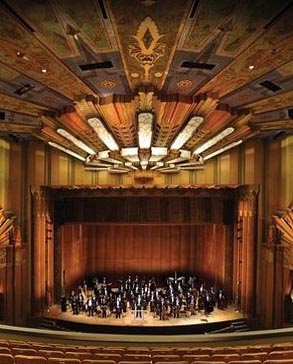

Charlotte: You have been a conductor for about twenty years now, and have worked with many different orchestras all over the world. Can we begin by asking how you see the role of conductor? People will be familiar with the image of a person standing in front of an orchestra, and they will probably have noticed that the conductor uses their arms quite a lot. But beyond that, they may not be totally familiar with what the role involves. James: It’s not a one-word answer, unfortunately, but rather more complicated. One of the words I prefer to avoid is ‘maestro’. This word evokes the old-fashioned notion of a formal figure, a dictator ruling by fear. Thankfully, orchestras have evolved, and those behaviours are not acceptable any more. But although the way the conductor works has changed, in essence, what we do has not. I would say it’s probably more akin to a theatre or movie director who is actually involved in the performance. We’re not just commanding ‘play this like this and that like that’; we’re hearing what the musicians offer. If we’re working with a good orchestra, there are maybe a hundred musicians in it who are all highly trained, skilled people, each offering something special when they play. Perhaps the biggest task for the conductor is the study of the score; looking at the music, getting to know the composer, getting the music into our bones. But I try to avoid the word ‘interpretation’ when talking about this process, as it suggests one individual’s vision being imposed on the music. The reality is that we study the score deeply and develop a vision ourselves, but then we meet an orchestra of real live human beings who all have their own opinions. Our job is to align those two things into something that works organically and beautifully. Robin: Maybe there’s a key in the actual word ‘conductor’. Like an electrical conductor that conducts a signal… a lightning conductor. James: Exactly. I love this idea that a conductor is, in fact, a conduit, managing different energies between the score, the composer, the music, the audience and the orchestra. And it is extremely difficult to do it well. As musicians will tell you, the baton makes no noise, which unfortunately supports a mythology that conducting is easy. But there are probably only a handful of people in history who have done it really well. It is rare that an orchestral player will complement a conductor, but if they do, they might say, ‘Yes, they are a good conductor because they don’t get in the way.’ The mantra of my old teacher Jorma Panula – the great Finnish conductor – was always: ‘help, but don’t get in the way’. I think a really good conductor works on a level that the musicians are not even consciously aware of. It’s the Taoist principle of leading without leaving a trace. Under great conductors, the musicians will feel totally free.  James conducting the Spokane Symphony in Dvorák’s Cello Concerto with guest performer Yo-Yo Ma on 6 September 2023. Photograph: Courtesy Spokane Symphony

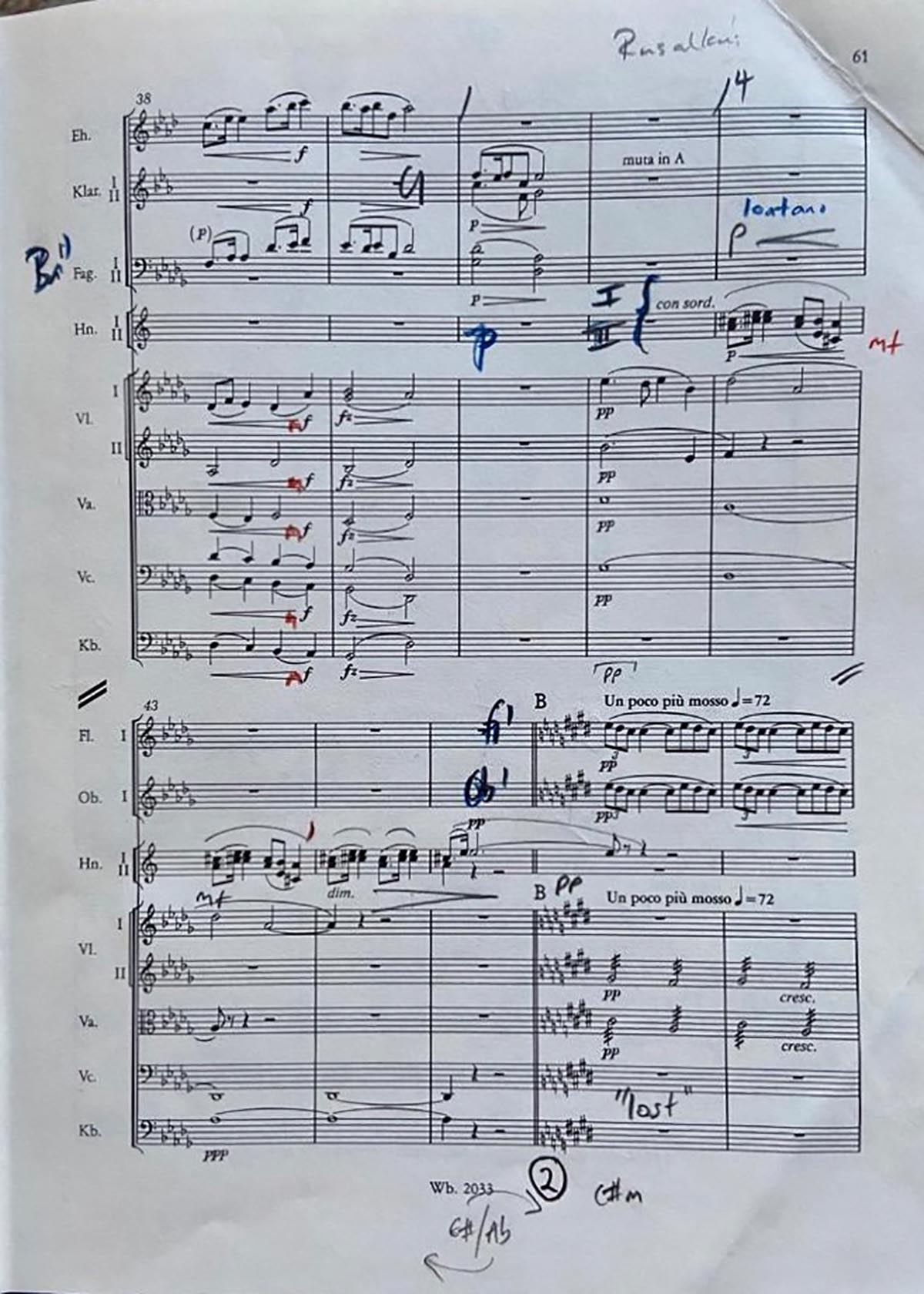

Conducting as a Dialogue. James: One of my great heroes, the late Bernard Haitink, who I was very lucky to know a little, said that he couldn’t influence a musician until they had influenced him. And this resonates with my own understanding. Conducting is always a dialogue. You offer something, the orchestra responds in a certain way, and then, hearing them, you tailor what you do to direct and encourage the sound. You mentioned that what people see the conductor doing is waving their arms around, but it isn’t a case of ‘this gesture equals that sound’. Our job is to be very finely tuned to the music once it is in motion, and to help it go where it wants to go. Haitink also said that performing music was like building a house. You go in with the plans – maybe some of the walls are there, but there’s no roof on it and the windows aren’t in place. The conductor must have a firm overview of the plans and ensure the most supportive architecture as the music builds. For example, if you’re conducting a movement of a Bruckner symphony, it may be forty minutes long, but the symphony itself may be no more than an hour or so, so you need to pace it very carefully. If you stop and smell every flower, the architecture of the piece collapses. Robin: In many musical ensembles – chamber groups, for example – there isn’t a conductor. Obviously, these are on a much smaller scale and the players are physically close enough that if their musicality is sufficient, they can work together and all hear what is happening. It’s like a conversation that everyone can follow. But presumably with a much larger force, like an orchestra, you need someone there to aid communication? James: It depends. I would say that most half-decent orchestras can play a great deal of the repertoire without a conductor. So, the question for me is: what extra thing am I adding? And I would answer that we are bringing the players into harmony by helping them listen to each other. Each musician has their own individual lines in front of them: the first oboe player, for instance, only sees the first oboe part, with cues to help them count rests. Only the conductor has the full score during a performance. There are some conductors – the rare ones – whom orchestras adore. Like Bernard Haitink, or Neeme Järvi who was another of my teachers: both very different musicians, with totally different ways of approaching music. When they stood in front of an orchestra, they brought something special – a quality, a magic, a sound – that was additive and not just on a practical level. So, more important than the practical aspect – the pacing, volume, etc. – is what we’re bringing from ‘behind’ the notes. Charlotte: How do you prepare yourself in order to do that? James: I’d say that my primary relationship for a long time is with the score. I spend a lot of time getting into the music, understanding it, reading about the composer. I want to feel a personal relationship with them, which is very often not helped by the fact that they’re dead! In studying the score I feel I am kind of reverse-engineering the ink on the page, back to what is behind the notes. The notation on the scores is astonishingly free, actually: it tells you the pitch, the relative note lengths, the relative loudness – but there’s an awful lot of room for manoeuvre, even with rather pernickety composers such as Gustav Mahler, who writes very detailed instructions. But ultimately, reading the score is only half the preparation. Performance is what allows the music to emerge, because you cannot capture the actual essence of music in notation. You have to perform it.  The score of Dvorák’s Symphony No. 9 in E minor (“From the New World”, Op. 95, B. 178) with annotations by James. Opening a Door to the Music. James: Well, perhaps this addresses something more spiritual. I’m not sure if I can answer your question exactly, except to say that I believe that there is a greater consciousness that we as individuals are usually separated from by our own sense of ourselves. Great art and music dissolves that barrier, allowing us to touch on something transpersonal, something above ourselves. A latter revelation, and a transformative one for me, has been that once a piece of music is in motion, it has a will and a life of its own. Somehow, the music is already happening when we meet it as musicians, as if we just open a door to where it is already playing. I see my job as conductor as listening at that level, and to let it evolve in the way it wants to go. Robin: The classical canon is loaded with an enormous amount of baggage around ‘style’, ‘idiom’ and ‘period’, with each piece being shaped and marked by a kind of time stamp. To what extent do you feel required to bring out the stylistic aspect of the music’s era? James: Whether one goes down that historically-informed performance route is a significant consideration. I don’t think I could possibly perform Bach in the way that they played it in the 1950s. That would feel totally wrong. But at the same time, it is not right to be so dogmatic about historical accuracy that we remove the spirit of the music. We have to remember that we’re not listening with 18th-century ears – we’re listening with 21st-century ears, and so there’s a lot to unpack in this area. What I do find rather sad is that the world’s best orchestras used to have very different sounds. You could tell them apart. As we’ve become more based on finding ‘the sound’ for each individual composer or piece, orchestral styles have generally become less distinct. Of course, you can still hear some differences: the Vienna Philharmonic, say, have slightly different instruments from other orchestras. Their sound has not changed, and that’s their big thing. Robin: Because a German oboe sounds different to a French oboe? James: Absolutely. And the Viennese oboes, again, sound totally different, and so on. And I love that. There is still some difference in sound between European and American orchestras, because the historically-informed performance revolution was a bit more ubiquitous in Europe. When I work with a European orchestra on a Mozart symphony, for example, I’ll anticipate a clean, leaner sound. But in America, where I have conducted with several orchestras, I have noticed that they often still play rather ‘full-throated’. If I am guest-conducting, it might not be considered respectful to alter the sound. Paavo Järvi, Neeme Järvi’s son, observed that this would be like going to a friend’s house and rearranging the furniture! As music director, on the other hand, I have a responsibility to consider the sound of my own orchestra into the future, and work with them in this way. Charlotte: Can you explain the difference between being a music director and a conductor? James: A conductor might work for a week here and there as a guest with different orchestras. A music director is the primary conductor of an orchestra and has responsibility for its overall artistic development: the artistic programme, hiring new players, fundraising, etc. I currently spend about twenty weeks a season in Spokane, and during that time I am conducting my own concerts as well as maintaining and developing donor relationships, doing educational work and planning media appearances and presentations. Before my concerts I also give a free public talk, called ‘the Lowe Down’, where I provide some historical and musical background to what we’ll be playing. These have been pretty well received, and I think people enjoy having more context for what they hear in the concert. Robin: And is that element of contextualisation or translation something you provide in musical performance as well? Or do you prefer to stay out of the way and just allow the music to speak for itself? James: Bringing the music to earth is an important part of what I do, but in the performance itself I think it’s vital that I do not interfere. Again, the Tao says that ‘Running a country is like cooking a small fish. You shouldn’t poke it too much.’ An orchestra should also not be poked too much, because the more inorganic the music becomes, the fewer people it will resonate with. Ideally, the listener brings something of themselves which connects with the music. Umberto Eco called the novel ‘a machine for generating interpretations’, and so similarly our understanding or interpretation of music comes through all our experiences of life, which are unique to us. Every individual in an audience will be having a slightly different feeling about the music they hear – and that’s as it should be. Charlotte: You have mentioned the influence of Taoism and Zen several times. How have these traditions played a role in shaping your understanding of what you do? James: Predominantly it is the idea of music flowing in its own way. My all-time favourite conductor is Carlos Kleiber, and I was thrilled to read that his favourite book was the Chuang Tsu. He was very influenced by Taoist philosophy. I myself have found the first words of the Tao Te Ching very helpful in thinking about music: The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. In essence, this says that ‘if you can put it in words, it’s not the real thing’, and that’s key to understanding music, because it does defy language. I loved Leonard Cohen’s response to the question, ‘What’s your new album about?’ He said, ‘If I could tell you that, I wouldn’t have had to write the music.’ I feel that music connects us to ourselves and others in a uniquely profound way. And great music has the ability to bring us into contact with something much greater, without language or explanation. In good performances, there are moments of what I would call communion; when an audience and an orchestra are really ‘there’ together. You can feel it palpably. Even though my back is turned to the audience, I can feel when an audience is there with me, and I feel it when they’re distracted, moving around, coughing or on their phone. Some of the most beautiful moments I’ve experienced in my life – not only in music – are at the end of a profound piece, such as Mahler’s 9th symphony, when it dissolves into silence and the entire roomful of people just sit in that silence, which can last for a minute or two minutes until somebody breaks it – usually the conductor puts the stick down. We sit in this incredible moment of presence with each other. Charlotte: Is that because in that moment the truth of the music has been met, somehow, in the confluence of the players, the conductor, the audience even? James: Yes, I think it’s that the music has brought us all to the same point. There are times when something just descends and it’s impossible to describe. You just know it when it’s there. Again, Haitink said this: you can’t make it happen, you can’t force it, you just have to be open to it when it arrives, and be very careful not to break it or disturb it.  James conducting the West of Scotland Schools Orchestra, one of his many projects with young musicians. Photograph: WSSO

Music for Everyone. James: Music has played a vital role in our shared cultural life for millennia, and I think it will always do so. And it’s not just classical music that does this. All kinds of music do it, and I wouldn’t want to give the impression that classical music is an inherently superior form. I feel that great music is great music, in whatever the format it comes in. Charlotte: Do you think it matters that most people now are listening to music remotely, either digitally or by watching a video of it? James: I appreciate and listen to recorded music a lot, and I’m grateful that it is so widely available. But I find the professionalisation of music quite sad. Music has become a thing that most people absorb – often passively – rather than actually doing it themselves. This is a loss, as playing music can have such a transformative effect at any level. It used to be that music was predominantly something you took part in. Many people played the piano or sang, and every household would have some kind of instrument. All our grandparents and great-grandparents would be able to play something. In those days if people wanted to hear the new Brahms symphony, they had to go and buy the piano reduction or the score and play it for themselves. Or they went to a performance. Music is ubiquitous now. Even when you go to the supermarket there’s music playing. In a way, that has cheapened the experience. But, on the other hand, music is not just a rarified, holy art form: it is also a tool. In the same way that the Coop sends fake baking bread smells around, they play piped music to keep people energised and happy in that space. And using music like that is also fine. But most of all, I wish that actually playing music had not become so rare – as playing with others, even as total beginners, enables you to have musical conversations in a language that is beyond words. And this is so valuable. Robin: I remember the phrase ‘le bon goût s’apprend’ – ‘good taste is learned’. Classical music perhaps gets described as elitist because it requires some work to get into, and if you want to learn to play it, it can be a long and difficult road. There is a process of learning, for learning beauty and learning taste. James: Yes. I would say that elitism is not playing Bach; elitism is keeping it to ourselves. If you’ve got one ear that kind of functions and a beating heart, you’ve pretty much got all the apparatus you need to understand classical music. It’s just a question of listening to it and accepting that not every piece is going to appeal to you. You can’t listen to one piece and say ‘I don’t like classical music.’ That would be like watching one film that you aren’t keen on and saying ‘I don’t like movies’. And if you want to go further and get into the nerdy undergrowth, which is where I like to spend my time, it has the potential to be an incredibly rich and beautiful experience. Nowadays, exposure to classical music is a big problem. People bemoan the lack of music education in schools but I would say there is a greater lack of exposure. The first thing is hearing classical music at all. Charlotte: I can see that you feel passionately that everyone should have access to music. And I know that you work with US schools and youth orchestras in your current role, and also with youth orchestras in the UK, such as West of Scotland Schools Orchestra and the Nottingham Youth Orchestra in your home town. James: As a musician I do feel that it’s my duty to pass on the spark. With my orchestra in Spokane, we have a lot of education outreach programmes – not just for kids but for people of all ages. Certainly, in terms of young people, hearing great music of any genre has the power to take them out of themselves and into connection with something higher. Having an aesthetic sense, whether it’s with the flowers in our garden, the food we’re eating or the music we’re listening to, makes our lives richer and more connected in this world. It also makes us feel small – in a good way. Robin: I was reading the other day about the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, who’s passionate about spreading this music. He has travelled to parts of East Africa, to small towns, even busking in market-places. It could seem a bit pretentious, being an international superstar pretending to busk in some poor town, yet he is absolutely committed to getting his music to more people, particularly those who don’t have a ‘classical’ or European background. And from what I could see, many have responded with great enthusiasm to it. James: He just came to work with us at Spokane in September, playing the Dvorák cello concerto. It was a deeply transformative and joyous experience for everyone in the hall that day. He has a generosity and enthusiasm for drawing people together that is deeply infectious. He has also transcended technique, the engineering side of our work, so that he’s entirely free to simply connect. As professional musicians we often get obsessed with the engineering, as we are expected to perform with 100 per cent accuracy, so being reminded of our deeper mission is extremely important. What I find interesting about him is that he studied anthropology at Harvard. His musicianship comes through the human connection first and foremost, rather than questions such as ‘what did this 18th-century source say about how a particular Bach cello suite might have sounded at that time?’. I think that’s why he’s such a powerful artist. Robin: And he originates from China and so is not the standard European classical music representative. In a way he’s making the music more globally relevant. James: Absolutely. The other thing that’s hugely important about music is that I can go and work with an orchestra in countries where I don’t speak the language, and we can understand each other perfectly well. Music is a universal language – beyond any spoken language – and that’s one of the many, many reasons why it’s so important for us to look after and nurture this art form.  Cellist Yo-Yo Ma performs at a subway station in Montreal, Saturday, December 8, 2018. Photograph: The Canadian Press/Graham Hughes/Alamy Stock Photo

The Future of Music. James: I think it’s always evolving. I’m very happy to see it’s becoming rather more diverse. Finally, women conductors seem to have become the norm, which I think is wonderful, and I hope it will continue to naturally evolve. My bigger worry is about what’s going to happen to the artistic institutions that support the music. You see all the government cuts that are happening in the UK, and the funding drying up in the US where orchestras and concert halls are supported by private organisations. This is of deep concern to me, because a lot of our institutions are very cumbersome and don’t react quickly to a new world. So, I’m more worried about whether there are going to be orchestras for us to work with. Robin: Could AI could ever replace a conductor? James: Maybe not as such, but what could very easily happen is that AI could replicate the sound of an orchestra. If I listen to a certain Hollywood composer who currently writes lots of scores, you can tell where it switches from a real orchestra into the electronic version. But I think very soon we won’t be able to tell the difference. And then there will be AI writing music. The recent Hollywood writers’ strike is just the tip of the iceberg. Maybe in a few years they won’t need to hire musicians to play the soundtracks for the new Indiana Jones movie; they’ll just have an AI write it in the style of John Williams. Charlotte: That is a disconcerting prospect, that future listeners might not know the difference between a real orchestra, or real players, and AI. From all you’ve said, it seems that we run the risk of losing something far greater than the entertainment that music brings. James: Yes, it is so important that real music – music shared live in front of an audience – continues to be available to people into the future. What really good music can bring to people is a taste of beauty and a sense of something greater than themselves which helps them grow. The more people have that available to them, the better the world in which we live will be.

|

||

|

|